Any classical string player who has ever attended an improvisation workshop led by Christian Howes will tell you that it is a life-changing experience. In fact, for most classical-only players, the very thought of attending such a workshop is a radical idea in itself; after all, improvisation is generally learned in a totally different environment, and cannot be taught formally. Simply put, most players believe improvisation is just too free-form to actually be taught.

One session with Christian Howes, gently introducing the concept of improvisation, articulating an easy-to-understand structure, and convincing classical players that improvising does not just “fall out of the sky”, quickly dispels that notion and puts classical players at ease. Once a player realizes that improvisation can indeed be taught, the creative doors open.

Christian’s genius is the same as that of all great teachers because of the pedagogy that he employs, a pedagogy that he created. In this third installment for SHAR in his series about becoming a Total String Player, Christian describes his brilliant way of learning how to approach and master one of the most important challenges required in improvising music: Chord changes.

Becoming a Total String Player: the Elephant in the Room

By Christian Howes

How do we, as classically trained string players, overcome our knowledge gap related to improvising over chord changes?

It’s the elephant in the room for most of us, and so often misunderstood.

Finding a good pedagogical solution for this problem has been a major focus of my work in developing the Creative Strings curriculum- so important that Berklee adapted much of this into their proficiency requirements for string majors ten years ago.

Although it’s a bit intimidating to address such a big question in a single article, it feels right to take it on now in relation to my series for Shar on “becoming a total string player.”

If you haven’t already, you can refer to my prior posts in this series to get caught up.

The first article lays out four broad components of the curriculum, and the second addresses psychological blocks that hold back many classical string players.

Several resources on the subject, including courses and ebooks are now available here at Shar.

Furthermore, an exhaustive library of Creative Strings curriculum is available via free 30 day trial at Creative Strings Academy.

The Fundamentals of Harmonic Fluency

Mastering harmony consists of internalizing all the possible relationships within a given chord or scale, AND quickly recognizing the points of connection between one scale or chord and any number of other scales or chords.

Think about that. Maybe read it again. It sounds simple, right?

Next, I’ll explain it in terms of “proficiencies,” i.e., things you will be able to do once you have mastered harmony:

1) The ability to quickly recognize and find all the notes of a given chord, or scale, anywhere on your instrument (ideally in every position), and to express the relationships between notes in the chord (or scale) in many iterations.

Application:

Given any chord symbol, you should be able to both arpeggiate notes from the chord and play double or triple stops from the chord in various iterations. Given any scale (or key signature), you should be able to play notes from the scale in various iterations or patterns, via single notes, double stops or triple stops.

2) The ability to quickly recognize the nearest notes available when resolving from a tone in one chord to a tone in another chord.

Application:

Given any progression from one chord to another, you should be able to express the proper voice leading relationships via a mixture of arpeggios, dyads, triads, and scalar shapes across these two chords, whether ascending or descending.

Using Only Your Ears is Not Enough. . .

A common mistake classical players make (and I see this often), is that they assume they will be able to improve recognition of harmony by using their ears. More specifically, they tend to think, “If I just listen harder, I’ll get it.” Instead of doing methodical ear training exercises (such as one might receive through an ear training class while doing a jazz studies degree, playing fiddle music, or even while growing up in a Suzuki program), many classical musicians think they should “keep trying” to improvise over given tunes, and that over time their ears will improve.

Even if they could use an ear-based approach to deal with this, which is possible, most people don’t implement this approach effectively. Instead, they continue to beat their head against a wall, making very little progress, eventually giving up.

This is a mistake that I made early on. Back then I might play the same tune for ten years, without ever really getting better at playing the tune or actually learning the progression.

A variation on the problem of internalizing the harmonic progression within tunes has to do with ingraining a new style of music. Musicians confuse the issue of learning a new style with the separate issue of learning the harmony.

These are separate problems.

In fact, you can take the same harmonic information, the same song, and arrange the song in many different styles. The harmony will stay fundamentally the same. What changes is the rhythmic treatment of the bass line, inner voices, and melody. All the more reason to compartmentalize these separate questions, re: harmonic internalization vs stylistic or rhythmic internalization.

I used to think, “Listen to more jazz recordings and eventually it will rub off so that I can sound authentic in the style AND confident in the chord progression.” It didn’t work, and finally I changed my approach.

Here’s the tweak in approach that helped me: While listening to a tune, read along to the chord chart. That way, your ear will get a helping hand. Reading the chord chart along to listening to the performance will help you internalize the harmonic form of the song much faster, and it will help your ears expand as well.

Let’s Talk About Ear Training

I grew up studying Suzuki, and like most Suzuki kids, while studying book four, I quickly came to know the Book Five pieces simply by hearing them played in my house all the time. This is an awesome component of Suzuki and other ear-based methods of study. The problem is that it doesn’t go far enough. I didn’t become aware of how limited my ears were until I started to try to hear music beyond my comfort zone of the Suzuki repertoire.

And let me be clear that to this day I still love the Suzuki method. A Suzuki dad, both of my kids have been trained by wonderful Suzuki teachers. Any criticism of Suzuki from me is only meant as encouragement to build on what I consider to be a wonderful method and community.

It turns out that Suzuki kids are taught to hear and recognize very specific things - usually classical sounding melodies in the register of the violin.

Similarly, for kids taught in fiddle styles traditions, specific melodies (and some chord qualities), are embedded deeply in the ears while leaving a big gap in other types of melodies and harmonic colors.

Once I joined a rock band I soon discovered the limits of my ear as follows:

- I couldn’t hear timbres outside the violin or piano (such as voice or guitar)

- I couldn’t recognize notes below the register of the violin

- I couldn’t recognize chords

- I couldn’t recognize melodies that sounded “different” than the familiar classical melodies

Since I was 15 and didn’t know any better, I began testing and working my ear out in different ways. I developed strategies to build on my Suzuki foundation, and my ability to recognize registers, timbres, harmonic colors, and broader melodic language developed. Of course, it’s still developing.

If you want to improve your ears, great! You can do so by transcribing the chord progressions on Suzuki tunes, fiddle tunes, holiday tunes, pop tunes. You can do it by transcribing melodies and solos from music that is unfamiliar. Perhaps a fiddle solo or a melody by Charlie Parker or a rock guitar solo.

You will expand your listening this way, and I highly recommend it, but it still will not be the fastest way for you to master harmonic relationships. The fastest way to do this is by combining your ears with your ability to read. Reading from the page will allow you to work through the materials and memorize them so much faster, and in the process, it will help train your ears. This will create a positive cycle that builds on itself.

Think about simple diatonic triads as falling onto a grid. The piano is a natural physical sort of grid that makes it easy to visualize this. The neck of a violin, viola, or cello is not. You should aspire to visualize or conceptualize that harmonic grid fully on a staff, a piano, via the way it sounds, and across the fingerboard of your instrument.

This is important: Having the grid on paper is the easiest way to get this process going. The dots on the paper effectively provide the same support as training wheels on a bike.

Reading Chord Stacks to Augment Your Ears

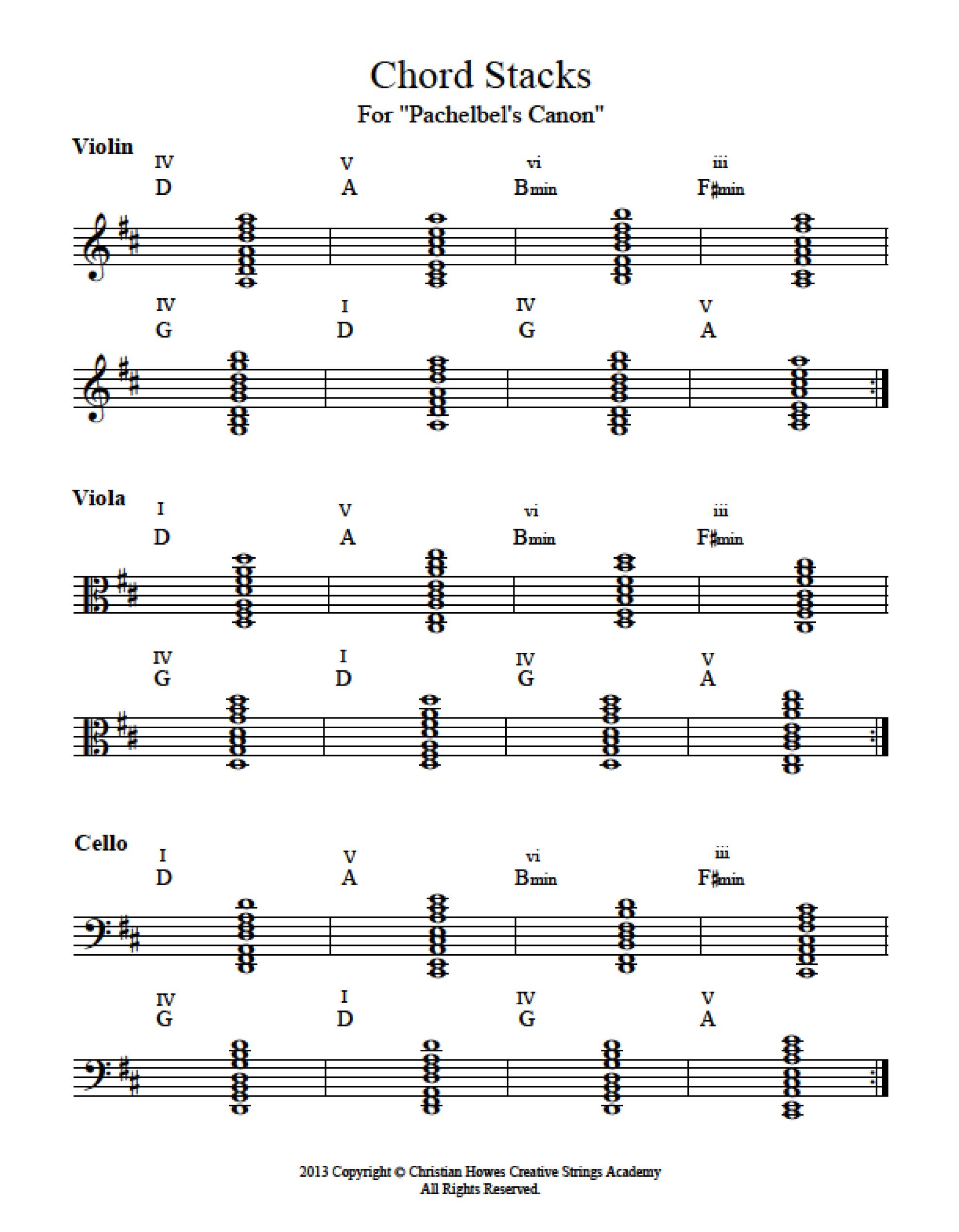

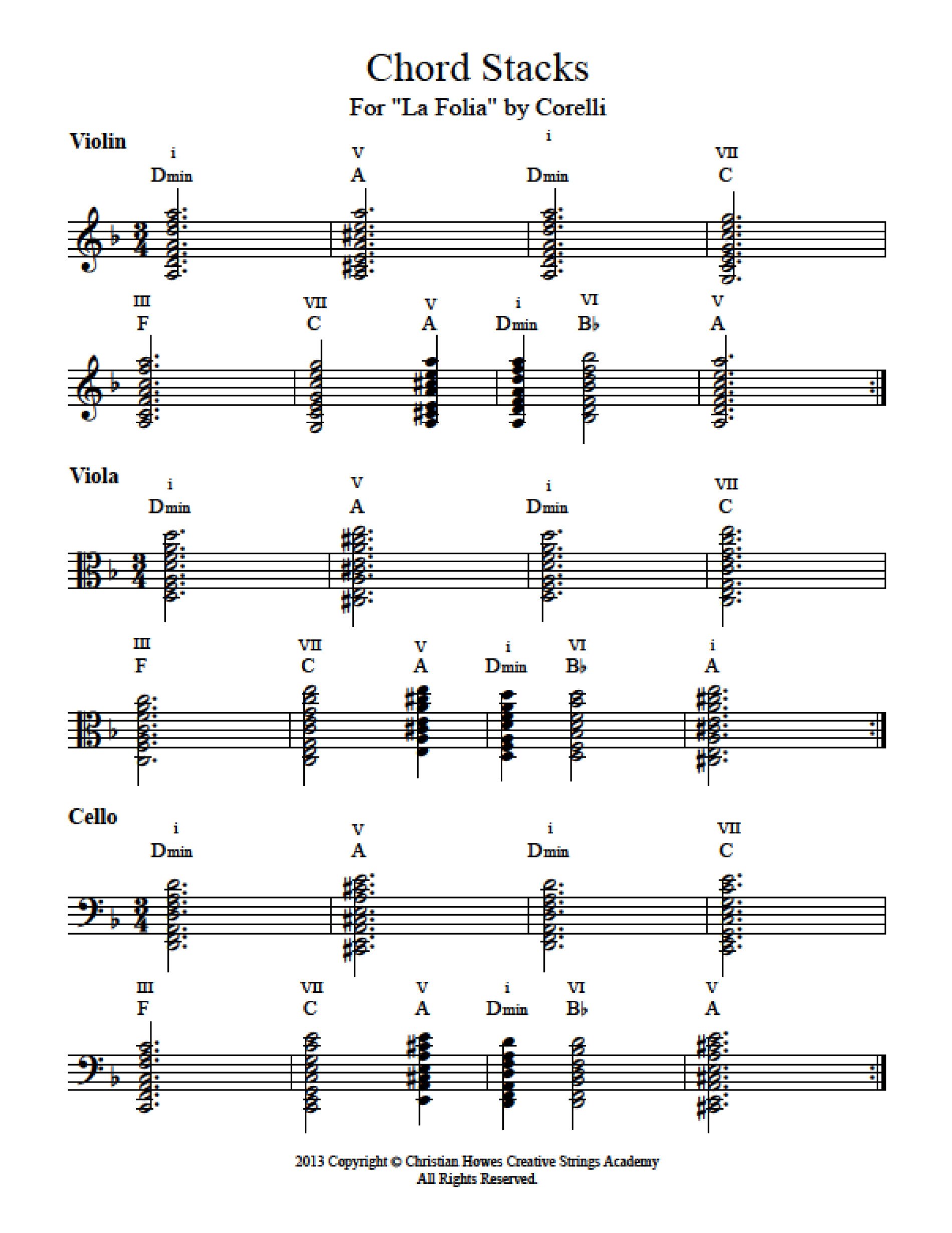

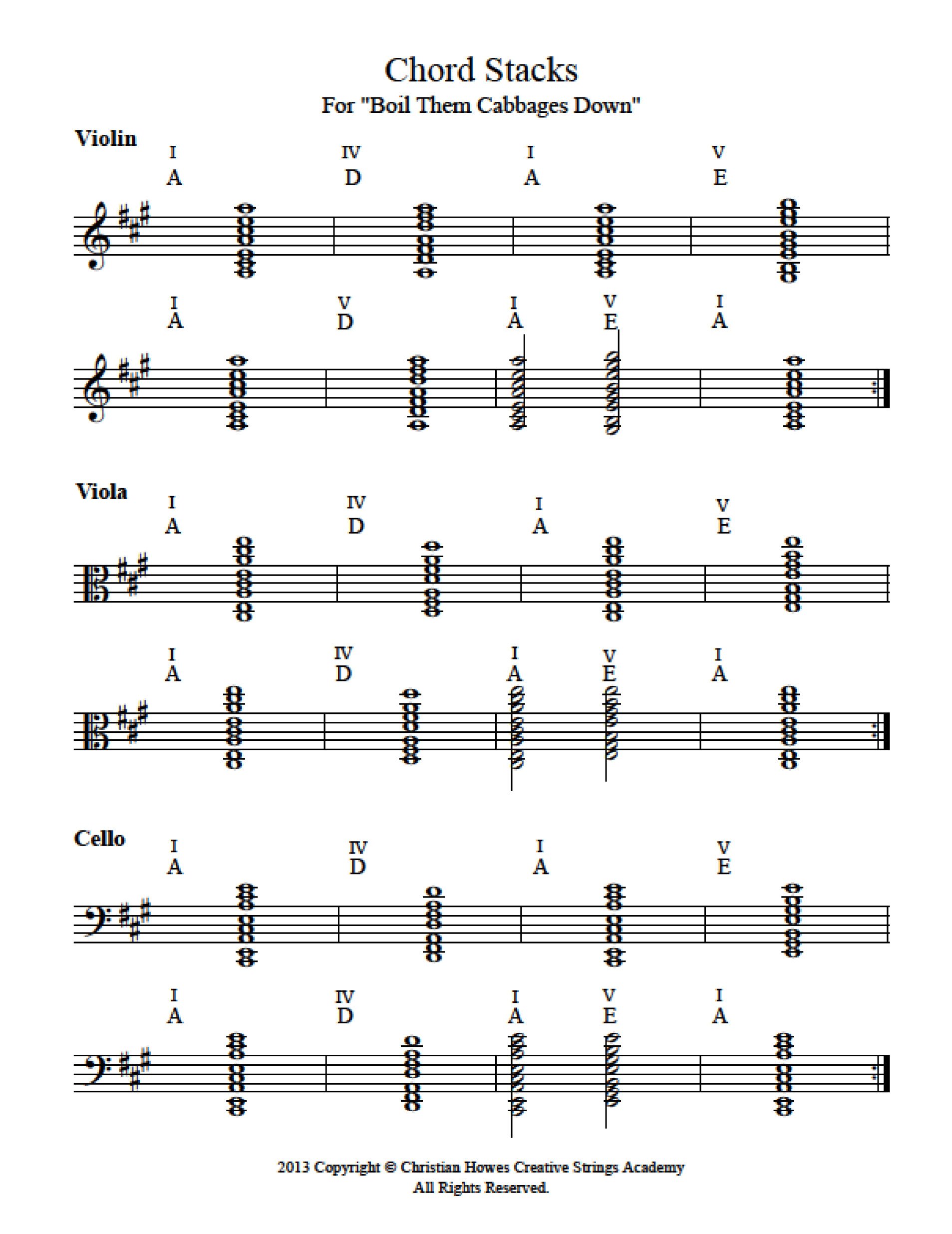

Specifically, the tool I developed to do this is something I call “Chord Stacks”. The key to a chord stack is the stacking of ALL the notes in a triad across extended range, first position, of your instrument. When you SEE the stacks on a staff, you can quickly identify all the voice led combinations within one chord as well as between two or more chords.

Here’s what the stack looks like for Pachelbel’s Canon:

Here’s what it looks like for “La Folia”:

Here it is on “Boil Them Cabbages”:

If you look at these it may seem somewhat obvious, but the critical mistake that so many teachers and classical players make is by only writing out the notes in root position, rather than extended range. Looking at the triads in root position completely misses the point of the need to voice lead chord tones from one chord to the next across your instrument everywhere in first position. And if you go back to my definition of harmonic mastery, this a critical component of that definition.

For any student with the ability to read, the exercises I developed in the course “Easy Tonal Improvisation” are transformative in terms of demystifying harmonic mastery. It makes all the difference between having a huge gaping hole around the subject of harmony and “getting it.” This made all the difference for me.

Once a student has gone through this critical exercise of using the chord stack visual aids, they can begin to use their ear and leave the paper. I can’t recommend enough how much these exercises have helped classical string players to make this critical leap forward in the journey of developing harmonic fluency. Get the course here.

After you make this jump, the next step is to begin committing individual arpeggios and scales to memory, beyond root position. The scales and arpeggios should be internalized in a much deeper way than what we typically learn through our classical scale books.

Two eBook resources I created help with this process:

Jazz Scales for Violin, Viola, and Cello

And

Arpeggios for Jazz Violin, Viola, and Cello

Finally, one can internalize/memorize the voice leading relationships between pairs of chords and full progressions.

The Violin Harmony Handbook expands on this to prescribe possibilities for advanced string players to express more complex iterations of harmony in technically demanding ways.

All of these products are available for purchase as downloads via SHAR. I suggest you begin with Easy Tonal Improvisation, and, if you wish to go deeper, or would like to add to your library of resources, get the three eBooks above.

Right now, you can obtain the three eBooks for free and stream the course, along with my entire Creative Strings curriculum, at Creative Strings Academy, via a 30-day free trial. During a limited time offer, I am also offering a free private Skype lesson to all new members (subject to availability).

Phew. That’s a lot, right?

Now, I have a couple questions for you, which I welcome you to answer in the comments.

- I’m interested in finding clear ways to talk about our musical journeys to become total musicians. Your feedback will help me in my continuing work as I develop clearer pedagogy around these problems that we all face as classical musicians.

- Do you feel that certain skills or information were missing from your classical training, and if so, how would you characterize the things you missed?

- If you feel that some things were missing from your classical training, what are the things you most wish you could learn to do as a musician, and why?

If you would like an immersive experience to explore these topics among a community of string players, please consider joining us at one of our Creative Strings Workshops. Click here to find a workshop near you.