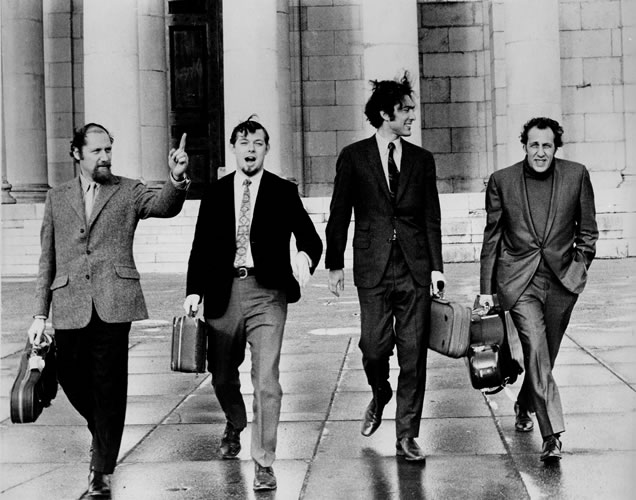

.jpg) The Guarneri String Quartet (photo by Erwin Fischer) and Charles Avsharian

The Guarneri String Quartet (photo by Erwin Fischer) and Charles Avsharian

Arnold Steinhardt and I have shared decades of wonderful times beginning back in the ‘60s when we both participated in the Marlboro Festival. We had also been on a tour together where he was the featured young artist and I was in the small chamber group backing him. While we both studied under Ivan Galamian at the Curtis Institute and Meadowmount, it wasn’t until later that we actually met and formed a long-lasting friendship. Our mutual friends were many… all fun-loving young men and women from the finest musical backgrounds. What we all had in common was our passion for music… and having as many laughs as possible. Over the years, I’m happy to report, our strong link of a warm friendship has never waned.

We have kept up our happy valued relationship over the years… through the family times, the Guarneri times, my SHAR years, publishing the quartet’s Beethoven quartets (including some hours of amazing, unpublished videos made in his family apartment in NYC), dozens of concerts, and continuing up through current times. I can’t remember a time when a broad smile wouldn’t spread across my face after having lunch together or just hanging out for a while. Arnold is just that sort of person… he brings out what humor and joy you have that might be waiting for a tickle. His writing continues to tickle me… and I am absolutely certain that it will tickle you as well.

Charles Avsharian

CEO, SHAR Products Company

Editor's Note: The following story by Arnold Steinhardt originally appeared on his blog In the Key of Strawberry and is republished with permission. Steinhardt is the founding member of the Guarneri String Quartet and the author of two books: Violin Dreams and Indivisible by Four. For more stories visit here or follow on Twitter.

"Jascha" by Arnold Steinhardt

Mr. Jascha Heifetz (born 1901, died 1987)

Violin Virtuoso Section

Heaven

February 2, 2012

Dear Mr. Heifetz,

Today, February 2nd, is your birthday. Happy birthday, sir, and my deepest thanks for the miracle of your artistry. I have listened to you play the violin throughout my entire life—actually my entire life plus nine months to be exact, since mother attended your concerts and listened to your recordings throughout her pregnancy with me.

Arnold Steinhardt (photo by Dorothea von Haeften)

Arnold Steinhardt (photo by Dorothea von Haeften)

In my childhood, I first heard you performing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto on our family’s records. The purity and shimmering tenderness of your playing brought unexpected tears to my young eyes. Then, as a young violin student struggling with the daunting difficulties of the instrument, your virtuosity astonished me. My teacher at the time, Peter Meremblum, you may recall had gone to school with you in Russia. Hardly a lesson went by without Meremblum’s making a comment about you. “Heifetz practices six to eight hours a day. Heifetz plays two hours of scales before he even looks at a piece of music.” The Heifetz campaign continued at home. My parents urged me to work harder so that I could become the next Heifetz. And when I slacked off they shook their heads sadly. How could I expect to be a Heifetz when I wasted time playing ball? At student concerts, “He’s no Heifetz” from my dad was the kiss of death.

The steady flow of comments was a testimony to your playing. You of all people know how difficult the violin is and that only a precious few have truly mastered it. Yet you had something beyond this. They say that an accident takes place when several unlikely things converge at the very same moment. You were the perfect example of a statistical improbability, or better said, a divine accident—the confluence of an ideal violinist’s body, an uncommon musical gift, and an obsessive need for perfection on every level. But there was something more. You seemed to have the nervous system of a humming bird: you could execute the minutest details at breakneck speed, shift moods in a split second, and recklessly dare all where others were prudently cautious. I listened to your recordings in disbelief. It was simply not possible for a human being to play with such wizardry. I despaired of ever even remotely approaching your level.

For a brief time as a teenager, though, I dared to think otherwise. I liked to play a little game with you, Mr. Heifetz, putting my assigned music on the stand and your rendition on the record player. It might be any number of pieces I worked on—Tchaikowsky’s Violin Concerto, Saint-Saëns’ Havanaise, or Sarasate’s Gypsy Airs. First I listened to you, shaking my head in wonder. Then I practiced the same piece myself. At the outset, the gap between us seemed too immense to cross, but with work I improved, and with improvement my spirits soared. I was catching up. Why, I was almost as good as you! Time to swagger over to the record player and listen to you again—you whose fingers moved so effortlessly, whose phrasing was like liquid mercury, whose playing seared with white heat one moment and teased playfully the next. “Jascha, Jascha”, I muttered despairingly as the record ended. You reigned over every would-be violinist, inspiring the industrious, crushing hope for those not supremely gifted, and stalking the lazy.

Finally, I heard you in person. Small, slender, but immaculately dressed, you stepped out onto the stage with a minimum of gesture. You did not accept our welcoming applause with deep bows but merely tilted your head in our direction. As you stood in front of the Los Angeles Philharmonic waiting for your solo entrance, you hardly moved, and even when you began to play, there were no excessive gestures, no grandstanding for the public, only those motions necessary to play the violin. Visually, you gave off a feeling of reserve, even aloofness, and yet the perfection of your delivery and the range of expression were astonishing. You challenged the most difficult of passages by rushing headlong into them—a display of fearlessness that took my breath away. Yet the lyrical moments had such tenderness and sensitivity that I wanted to weep. It was a performance of fire and shimmering light delivered in a container made out of ice.

Other violin virtuosos engaged me differently than you. When I listened to Fritz Kreisler, someone I know you admired greatly and who shares your birth date, I could easily imagine a benign and loving 19th century world lit by candlelight. The Hungarian violinist, Joseph Szigeti, my last teacher, affected me no less deeply but quite differently with his keen intellect and touching nobility. But when you played, Mr. Heifetz, my heart raced and the palms of my hands broke out in sweat. The improbability of your performances was almost too much to bear.

The Guarneri Trio (photo by Erwin Fischer)

The Guarneri Trio (photo by Erwin Fischer)

I risked listening to you only occasionally as my years in music school came to an end and I prepared for a concert career. Your playing was too seductive, too hypnotic. I wanted to sound like you—a common if forgivable trait in young players under the spell of a great artist. It was, of course, an impossibility, but also highly inadvisable. There could be only one Heifetz. My job was to become Steinhardt, whoever he might turn out to be and however long that would take.

Last February, a weekend seminar devoted to you took place in Athens, Georgia. Pianist Seymour Lipkin and I played a recital that included Dreams in the Twilight by Richard Strauss, an unpublished transcription of yours. The next day, God’s Fiddler, a new documentary about you, was shown. Afterwards, there was a panel discussion with Seymour Lipkin who had performed with you for U.S. soldiers during the Second World War (remember that scrawny but immensely gifted kid with the big glasses?), John and John Anthony Maltese, father and son, who are writing a book about you, Peter Rosen, the film’s producer, and yours truly. We had a lively enough discussion about you as a violinist, artist, and personality, but I couldn’t help thinking that you’ve been the subject of similar if less formal conversations over the course of my entire adult life. How many times have we musicians gathered together during rehearsal breaks, back stage before concerts, or over dinner and drinks to talk breathlessly about your performances of say, Paganini’s Perpetual Motion, Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy, Brahms’ Violin Concerto, Bach’s Chaconne, or easily dozens and dozens of other works.

Several of us who revere you, Mr. Heifetz, have coined an expression for that rare individual in any field, be it music, sports, chess, dance, etc., who has reached your exalted pinnacle of excellence. “He’s a real Jascha”, we’ll say, conferring our highest possible praise. In your case, however, that pinnacle apparently came with a price. We rejoiced reading about your earliest days as a child prodigy and loved seeing the home movies of you as a wildly successful and fun loving young man. But then came painful stories about how you began to change over the years. Jack Pfeiffer, who was both our Guarneri String Quartet’s and your record producer at RCA for several years, told us that you once called him to discuss your latest recording project. When the conversation ended, Jack apparently asked you how you were. “I called you,” you said. “You call me if you want to know how I am”.

Most of us would find it hard to imagine how much the public’s expectations and your self-imposed standards must have pressed in on you. Perhaps your iron-fisted resolve was what inadvertently began to separate you from people. Perhaps it led you, along with the devotion and kindness you often showed to your students, to become quirky, suspicious, and mistrustful of many of your friends and colleagues.

And yet, year after year, and despite whatever else was taking place in your life, you continued to play the violin like a God for me, for us. Seymour Lipkin said that despite the highly dangerous circumstances of the war raging nearby, not once in the dozens of concerts you generously gave for United States troops did you play less than your very best. Perhaps, it was only through the violin that you could truly communicate from your heart to each one of ours.

Although you passed away in 1987, I still listen to your records. Each time you play, my heart races, the palms of my hands begin to sweat, and I shake my head in wonder.

Happy birthday, and thank you, Mr. Heifetz. You are a real Jascha!