I'm not sure if you readers out there in the blogosphere subscribe to Richard Dare's blog for The Huffington Post. Dare is the CEO and Managing Director of the Brooklyn Philharmonic and he has a surprisingly sharp and entertaining blog going. (I say "surprisingly sharp and entertaining" because he's also a business whiz; it's kind of unfair that he's got both such a good head for business and a sharp instinct for art.)

I'm not sure if you readers out there in the blogosphere subscribe to Richard Dare's blog for The Huffington Post. Dare is the CEO and Managing Director of the Brooklyn Philharmonic and he has a surprisingly sharp and entertaining blog going. (I say "surprisingly sharp and entertaining" because he's also a business whiz; it's kind of unfair that he's got both such a good head for business and a sharp instinct for art.)

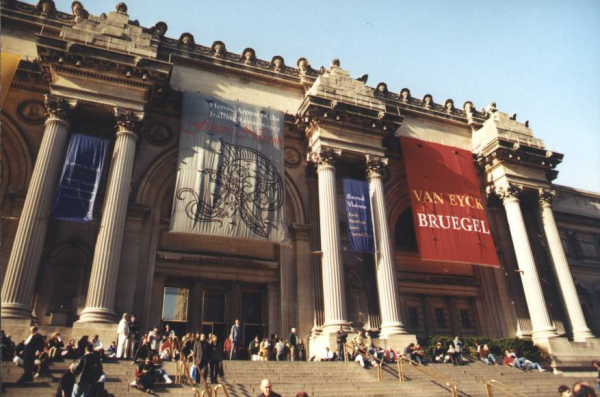

I was browsing Dare's backlog of entries and I came across one from March titled "Brave New World: Who Muzzled All the Artists?" In this article, Dare shares an anecdote about visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. When a particular painting catches his eye, Dare turns to the docent giving him tour and asks, "What does it mean?" The docent, either in autopilot or intent on having Dare think for himself, volleys the question back to Dare: "Well," she says, "what do you think it means?"

Dare expresses his annoyance with the docent. Why, since art and music are so powerful, won't artists and musicians just come out and say what their compositions or paintings mean? And why is it that when our scholars, critics, and experts review an opera full of "murder and rape, war and pestilence, political intrigue, backstabbing" only talk about "whether the soprano hit her high notes gracefully"?

These are certainly fair questions. And, of course, Dare has a few answers. One, that art has gotten too self-referential: these days it's always about other art and not about everyday life. Two, that dictatorships from the twentieth-century have forced artists to "hide" their meanings more often. And three, that ours is an age of TV and we've just gotten lazy as interpreters of high art.

I would add to Dare's list, though, that it's just plain hard to interpret art and music. For lack of a better phrase, there's a ton of stuff to consider. Does the intention of the composer matter? The historical context of the work? The response of the individual listener? The response of a group of listeners? The way the piece engages with a genre or form? What about music theory and higher-level criticism? In a way, the docent tried to privilege Dare's individual response to the painting, although perhaps she should have said "How does it make you feel as a viewer?" In any case, it's a lot to think about and feel. As David Foster Wallace would say, good art is a "brain-melter."

I'd add yet another, perhaps generational, diagnosis of our fear of meaning. We live in an age of irony and evasion. When I think of my friends (Generation Y) and my younger brothers' friends (Millennials), I know how we'd respond to Richard Dare's question "What does it mean?" We certainly wouldn't gush about the beauty of the painting; most likely we would slyly admit to being moved by the painting while mocking that emotional engagement. Let's say the painting somehow conjures the pain of new beginnings. My brother would probably say in response to it: "It's about how bad my cat's breath smells in the morning." Funny, yes, and in a way accurate, but ultimately unsatisfying.  Irony is just the tone of his and my generation. This is the age of Internet memes and YouTube absurdity and Twitter hashtags and lightning-fast anonymous responses. In addition, it's also the age of an overwhelming amount of information. The sheer weight of what others have said make the interpretation of art even harder. (I think of Malcolm Gladwell's article on Enron's collapse a few years back, and his diagnosis of that catastrophe: it's not that we didn't have the signs in front of us, it's that there was too much information to even know what was relevant.)

Irony is just the tone of his and my generation. This is the age of Internet memes and YouTube absurdity and Twitter hashtags and lightning-fast anonymous responses. In addition, it's also the age of an overwhelming amount of information. The sheer weight of what others have said make the interpretation of art even harder. (I think of Malcolm Gladwell's article on Enron's collapse a few years back, and his diagnosis of that catastrophe: it's not that we didn't have the signs in front of us, it's that there was too much information to even know what was relevant.)

So, what are we supposed to do? One of my favorite books on art and music is Real Presences by George Steiner. Among other things, Steiner argues that the best form of criticism is to make more art. If you hear a gorgeous violin concerto, the only way to truly and adequately respond to it is to write one yourself. I'm partial to his point, because it cuts through all the complications of interpretation, irony, and self-conscious criticism. You simply make other people feel what you felt.

sharmusic.com

Enjoy FREE 2-4 Day Shipping on your order of $30 or more! (shipped to the 48 contiguous states)

- Strings

- Sheet Music

- Suzuki

- Instruments

- Bows

- Cases & Bags

- Accessories

- Books & DVDs

- Case Accessories & Parts

- Chairs

- Chinrests

- Cleaner, Polish, & Cloths

- Digital Recorders

- Endpin Anchors & Stops

- Gear

- Gifts

- Humidifiers

- Instrument Stands

- Metronomes & Tuners

- Misc

- Music Stands & Accessories

- Mutes

- Peg Compound & Drops

- Rosin

- SHAR Workshop

- Shoulder Rests

- Shoulder Rest Parts

- Teaching Aids

- Tote Bags

- Digital

- Rentals

- New

- Learn

- Teach

- Log In