Arnold Schoenberg

September 13, 1874 - July 13, 1951

Arnold Schoenberg’s name often stirs up strong opinions. Some revere him as a genius who advanced music in the 20th century while others despise his often discordant music. As a music lover and performer, I often have a love/hate relationship with Schoenberg and his music. Schoenberg’s music is not very popular and it’s rarely played, but it holds an important place in music history.

Arnold Schoenberg’s name often stirs up strong opinions. Some revere him as a genius who advanced music in the 20th century while others despise his often discordant music. As a music lover and performer, I often have a love/hate relationship with Schoenberg and his music. Schoenberg’s music is not very popular and it’s rarely played, but it holds an important place in music history.

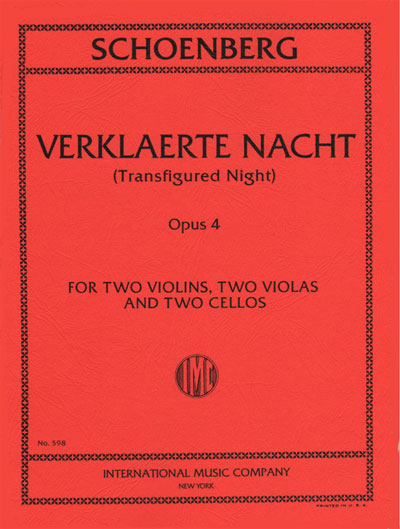

As a budding young composer, Schoenberg was largely self-taught. He did take counterpoint lessons with Alexander von Zemlinsky (and later married Zemlinsky's sister), but that’s about all the formal training he had. Schoenberg began to earn a living by orchestrating operettas. While doing this, he composed many of his own works, including the famous Verklarte Nacht. Around this time, both Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss took an interest in Schoenberg’s music and began recognizing him as an important composer. Mahler even became Schoenberg’s musical mentor, providing support and guidance even when Schoenberg’s music went beyond what Mahler understood or could agree with.

In 1926, Schoenberg began his appointment as Director of a Master Class in Composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Schoenberg decided to move to America with his family (he had a second wife and young children at this point). He began teaching at the Malkin Conservatory in Boston, but eventually moved to Los Angeles where he taught at USC as well as UCLA. He became a serious Bruins football fan (sorry, Trojans!). He eventually bought a house in Brentwood Park that was located across the street from Shirley Temple’s house. While living there, he met many well-known actors as well as notable performers, conductors and artists, including George Gershwin (who played tennis with him).

Despite what you might think, Schoenberg’s music is quite varied. His music can be roughly placed into three periods: late romanticism, free tonality, and his famous 12-tone system. One musical example of his late romanticism period is string sextet (and later, turned orchestral work) Verklarte Nacht (Transfigured Night). As a violinist, I have had the opportunity to perform this work twice. Initially, I dreaded having to play the notoriously crazy music of Schoenberg. The sheets of paper in my hand looked messy and complicated. I knew I was in for many painful hours of practice. However, the first time I heard a recording of this piece, I was astounded. I thought to myself, “This can’t be the crazy cacophonous music of Schoenberg!" and then, "I didn’t know that Schoenberg wrote such beautiful music!” This piece is definitely the “love” component of my love/hate relationship with Schoenberg. This work isn’t atonal, but rather extremely chromatic. It’s much more along the lines of Wagner, Strauss and other late romantics. Schoenberg based the piece’s content on Richard Dehmel's poem of the same name. It was also inspired by Schoenberg’s emotional experience upon meeting his first wife, Mathilde. There’s a special musical moment near the end of the piece when the poem’s characters love story culminates in gorgeous harmonies, breathtaking color and nuanced texture. The audience experiences a poignant moment where the world is transformed by the characters’ love.

Despite what you might think, Schoenberg’s music is quite varied. His music can be roughly placed into three periods: late romanticism, free tonality, and his famous 12-tone system. One musical example of his late romanticism period is string sextet (and later, turned orchestral work) Verklarte Nacht (Transfigured Night). As a violinist, I have had the opportunity to perform this work twice. Initially, I dreaded having to play the notoriously crazy music of Schoenberg. The sheets of paper in my hand looked messy and complicated. I knew I was in for many painful hours of practice. However, the first time I heard a recording of this piece, I was astounded. I thought to myself, “This can’t be the crazy cacophonous music of Schoenberg!" and then, "I didn’t know that Schoenberg wrote such beautiful music!” This piece is definitely the “love” component of my love/hate relationship with Schoenberg. This work isn’t atonal, but rather extremely chromatic. It’s much more along the lines of Wagner, Strauss and other late romantics. Schoenberg based the piece’s content on Richard Dehmel's poem of the same name. It was also inspired by Schoenberg’s emotional experience upon meeting his first wife, Mathilde. There’s a special musical moment near the end of the piece when the poem’s characters love story culminates in gorgeous harmonies, breathtaking color and nuanced texture. The audience experiences a poignant moment where the world is transformed by the characters’ love.

An example of the free-tonality period of Schoenberg's music is the famous Pierrot Lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot). It was written for a small ensemble with voice. The main character, Pierrot, sings about love, religion, violence and crime in a generally twisted and disturbing way; there’s almost a spark of insanity to the character. This piece utilizes a vocal technique popularized by Schoenberg called “sprechstimme,” which is basically somewhere between talking and singing. This work is not performed very often due to its difficult nature (the first performance needed nearly 40 rehearsals!). When I was presented with the opportunity to play its violin/viola part, I was excited by the opportunity to tackle this great work. My excitement came to a grinding halt once I looked at the music… yikes! Not only did I have to wade through pages and pages of music that was atonal, in high registers, and full of extended techniques, but I had to play viola on some movements! I am just a recreational violist, so this piece took an extra long time to learn (the “hate” part of my love/hate relationship with Schoenberg). I spent several weeks on just figuring out fingerings, bowings, rhythms and in general just trying to decipher all of the information on the page. Only then could I actually start playing and practicing it. My individual preparation, which preceded rehearsals with the other musicians, took a lot of time. I even marked my part with lots of colors to indicate where I had to switch from violin to viola and back, where I had to switch bows, what to listen for so I could make correct entrances, and the dynamics (which were sometimes buried in a mess of other musical markings). Simply put, this was complicated stuff!

An example of the free-tonality period of Schoenberg's music is the famous Pierrot Lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot). It was written for a small ensemble with voice. The main character, Pierrot, sings about love, religion, violence and crime in a generally twisted and disturbing way; there’s almost a spark of insanity to the character. This piece utilizes a vocal technique popularized by Schoenberg called “sprechstimme,” which is basically somewhere between talking and singing. This work is not performed very often due to its difficult nature (the first performance needed nearly 40 rehearsals!). When I was presented with the opportunity to play its violin/viola part, I was excited by the opportunity to tackle this great work. My excitement came to a grinding halt once I looked at the music… yikes! Not only did I have to wade through pages and pages of music that was atonal, in high registers, and full of extended techniques, but I had to play viola on some movements! I am just a recreational violist, so this piece took an extra long time to learn (the “hate” part of my love/hate relationship with Schoenberg). I spent several weeks on just figuring out fingerings, bowings, rhythms and in general just trying to decipher all of the information on the page. Only then could I actually start playing and practicing it. My individual preparation, which preceded rehearsals with the other musicians, took a lot of time. I even marked my part with lots of colors to indicate where I had to switch from violin to viola and back, where I had to switch bows, what to listen for so I could make correct entrances, and the dynamics (which were sometimes buried in a mess of other musical markings). Simply put, this was complicated stuff!

Allow me to share with you the madness that is performing Schoenberg: I had to buy a spare bow that I didn’t mind getting scratched, because there were points in Pierrot Lunaire where the was so much col legno (hitting the bow on the stick’s side and dragging the stick across the string) that I even had to put rosin on the stick to create a sound (don’t try this at home!!).

In my experience, I thought one of the most interesting things about playing Pierrot Lunaire was the paradoxical nature of the piece. You can see the paradoxes in several places: in the instrumentalists (who are both soloists and the orchestra), in Pierrot (who is both the hero and the fool), in the piece itself which is a concert piece (with lots of drama), the music which is performed as cabaret (with “speech” song), and in Pierrot’s gender (a male role sung by a woman). So yes, Schoenberg’s music is crazy, but was it worth it? I think so. It stretched my technical and musical abilities as a performer and I have to admit that the music has grown on me.

So let’s talk about the next period of Schoenberg’s composing: 12-tone technique (aka dodecaphony or 12-tone serialism). An example of his 12-tone period of music is the Violin Concerto. The basic rule of 12-tone composition is that you must use all twelve notes of the chromatic scale in an order you create, giving them equal importance (and you can’t leave any of them out!). Thus, the music avoids being in any particular key. There is much written about this compositional style and getting into detail about it is beyond the scope of this blog. Many people consider it to not be music because it’s a far cry from Beethoven or Brahms, but its merits are there. You just have to dig a little deeper and get to know Schoenberg’s musical language. In order to begin appreciating such discordant music, the listener has to move beyond any preconceptions they might have about music and just appreciate the energy that’s behind the music and in the performance.

Throughout his life, Schoenberg had an unusual fear of the number 13, called triskaidekaphobia. (Perhaps he was into 12 tones, because he didn’t want to deal with 13 of them?) Ironic that he was born on the 13th of September, died on the 13th of July, and died 13 minutes before midnight (although this last bit could be apocryphal). It makes me wonder if he worried himself to death.

Whether or not you love or hate Schoenberg (or both like I do), his historical significance cannot be overlooked. If you haven’t given his earlier works a listen, it may transfigure (pun intended) your opinion about this man. Happy birthday, Arnold!

Recommended Recordings:

Schoenberg by Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic

Verklarte Nacht / Variations for Orchestra

Deutsche Grammophon Label

Schoenberg by Hilary Hahn and Esa-Pekka Salonen with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra

Schoenberg Violin Concerto / Sibelius Violin Concerto

Deutsche Grammophon Label

Schoenberg by Christine Schafer and Pierre Boulez with Ensemble InterContemporain

Pierrot Lunaire

Deutsche Grammophon Label

Sources:

1. Lunday, Elizabeth. Secret Lives of Great Composers. Philadelphia: Quirk Books, 2009.

pg. 194-199

2. Barber, David. Bach, Beethoven and the Boys. Toronto, CA: Sound and Vision, 1986.

pg. 132-134

3. Wikipedia Article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arnold_Schoenberg