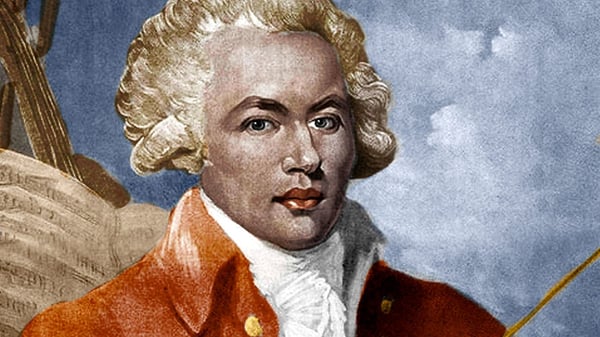

February is Black History Month, and SHAR wants to celebrate by honoring the legacies of renowned, yet underappreciated black composers and musicians. Each week, we will recognize and commemorate one composer who has made an impact on the musical world as we know it. To begin, we want to shine a light on Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, the first ever classical composer of African descent.

Born in the French colony of Guadeloupe in 1745, Saint-Georges’ mother relocated him to Paris at a young age, where he began his education and became a very accomplished fencer. He took up violin as a child, and while there is little official documentation regarding who he studied with, he soon became a celebrated violinist in an amateur Parisian symphony orchestra. He found a mentor in musician and composer François Gossec while playing with the Concert des Amateurs, a company which organized musical concerts, of which Gossec served as the director. Saint-Georges had his sensational soloist debut in 1772 where he performed his own violin concertos with the Amateurs. This made the Parisian public take note of him as a musician, and as a composer.

Saint-Georges composed a wide variety of pieces, beginning with string quartets that were inspired by Haydn’s earliest works. He also took an interest in writing duos and sonatas for forte-piano, violin, harp, and flute. It’s said that he composed pieces for cello, clarinet and bassoon, as well, but those compositions were lost. He also wrote twelve violin concertos, two symphonies, and eight symphonie-concertantes, a distinctly Parisian genre that he is said to have contributed to greatly.

His success as a composer and violinist was followed by his success as a conductor. After Gossec took over the direction of the Concert Spirituel, another prestigious Parisian concert series, he chose Saint-Georges to take over as director of the Concert des Amateurs. After two years under the Saint-Georges direction, the group was described as “the best orchestra for symphonies in Paris, and perhaps in all of Europe”. The Queen, Marie Antoinette, often showed up to their concerts unannounced, so the performers took to dressing in courtly attire in case she made an appearance. The Queen enjoyed Saint-Georges playing so much that he was one of the favored few musicians and elite invited to her salon for private concerts.

Soon after his success with the Concert des Amateurs, Saint-Georges abandoned writing instrumental pieces and shifted his focus to operas and plays. While working on his operas, he was hosted by the Duke of Orleans, at which point he shared a roof with W.A. Mozart, whose mother had just passed in Paris. It is said that, during their time of cohabitation, Mozart grew wildly jealous of Saint-Georges intellect, talent, and success. Some believe that the villainous Monostatos from Mozart’s The Magic Flute is an unkind tribute to Saint-Georges.

In no time at all, the French Revolution was underway. Though Saint-Georges led a regiment of black soldiers, he fared better than most. After suffering through imprisonment and threats of death, he managed to return home and worked to rebuild his orchestra in Paris. His health was failing, but he remained devoted to his violin in the final years of his life. “Never before did I play it so well,” he claimed, before he passed from illness in 1799.

Read the other blogs in our Black History Month Series!

Make sure to subscribe to our blog and follow us on social media where we'll continue to commemorate these notable black composers and musicians through the month of February!