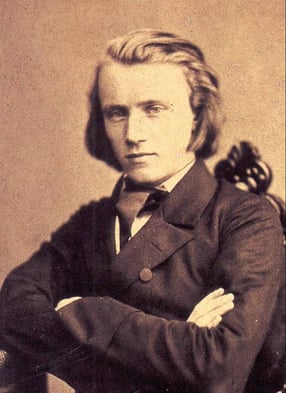

Think you know how to play Brahms? Douglas Woodfull-Harris, Editor for Orchestral and Chamber Music at Bärenreiter, gives us a preview of "the overwhelming amount of vital information" contained in the new Bärenreiter Urtext editions of Brahms. If you're serious about Brahms, or performance of Romantic music, you'll want to get your hands on these new titles from Bärenreiter.

I have worked with countless musicians and scholars on an array of editions over the last 25 years, but none has opened the door to understanding a composer’s music as widely as Clive Brown, Neal Peres Da Costa and Kate Bennett Wadsworth have in our new Urtext editions of Johannes Brahms’ works for one instrument and piano.

I have worked with countless musicians and scholars on an array of editions over the last 25 years, but none has opened the door to understanding a composer’s music as widely as Clive Brown, Neal Peres Da Costa and Kate Bennett Wadsworth have in our new Urtext editions of Johannes Brahms’ works for one instrument and piano.

My working relationship with Clive Brown goes back a good ten years to our collaboration on Brahms’ Violin Concerto op. 77. In Bärenreiter’s scholarly critical edition of the concerto, Clive provided performers with one of the most important texts on performance practice, particularly highlighting the close working relationship between Joseph Joachim and the composer. The edition is still the ultimate reference point for any violinist eager to understand how Brahms intended his music to sing!

Shifting the wheels ten years into the future, I am once again able to present a pioneering approach to Brahms’ music with new editions of his violin, viola and violoncellos sonatas. They contain an overwhelming amount of vital information and invaluable assistance to anyone seriously approaching this music.

Clive Brown’s Preface describes the origins, process of composition and history of pre-publication performances. This is followed by documentation of the publication and early reception of each work.

In addition to this in-depth historical foundation, each edition offers a Performance Practice Commentary written by Clive Brown and pianist Neal Peres Da Costa. For example the text on the G major Violin Sonata op. 78 draws on editions of the sonata made by both players who performed the work with or under Brahms’ supervision, such as Joachim and Franz Kneisel, as well as important students of Joachim’s such as Leopold Auer and Ossip Schnirlin. A chart of metronome markings found in the various editions is presented. Also you will find specific and practical information on Brahms’ musical esthetics: rhythm and timing, dynamics and accentuation, dots and strokes, slurring and non- legato, pedaling and overholding, arpeggiation and dislocation, string instrument fingering and string instrument harmonics and vibrato. This is followed by a measure for measure comparison of how these players understood the music and interpreted it.

In addition to this in-depth historical foundation, each edition offers a Performance Practice Commentary written by Clive Brown and pianist Neal Peres Da Costa. For example the text on the G major Violin Sonata op. 78 draws on editions of the sonata made by both players who performed the work with or under Brahms’ supervision, such as Joachim and Franz Kneisel, as well as important students of Joachim’s such as Leopold Auer and Ossip Schnirlin. A chart of metronome markings found in the various editions is presented. Also you will find specific and practical information on Brahms’ musical esthetics: rhythm and timing, dynamics and accentuation, dots and strokes, slurring and non- legato, pedaling and overholding, arpeggiation and dislocation, string instrument fingering and string instrument harmonics and vibrato. This is followed by a measure for measure comparison of how these players understood the music and interpreted it.

The music text has been critically edited and a Critical Report based on all known sources can be found in the Appendix of each publication.

The music editions are complemented by a booklet entitled “Performance Practices in Johannes Brahms’ Chamber Music” (BA 9600) written by Clive Brown on general issues of performance practice (violin and viola – Vibrato, Expressive Fingering, Bowing), Neal Peres Da Costa (piano – Melodic Emphasis, Texture and Agogics, The Evidence of Recording: Brahms’ Contemporaries, Pedaling, Brahms’ Damper Pedal Markings, Soft Pedal) and Kate Bennett Wadsworth (violoncello – Brahms and the Cello, Continuity and Change).

In summary these texts provide invaluable and unprecedented information to the understanding of Romantic performance practice in general.