Editor's Note: The following blog post originally appeared on Tarisio and is being republished with permission. You can find the original postings here: Part I, Part II

PASCAL LAUXERROIS & LIONEL TASQUIER

Two great bowmakers you’ve probably never heard of

by Richard Young, Vermeer Quartet

Not a single bow by Pascal Lauxerrois or Lionel Tasquier has ever been sold by a major auction house. And most American dealers have never even heard of them. Of those who have, it’s unlikely that any have actually held one of their bows. Yet according to most of their peers, no one was more gifted than these two archetiers. Benoît Rolland states emphatically, “On their best days, Pascal and Lionel were better than any of us.”

These two makers have more in common than their obscurity and the outstanding quality of their work. Both attended l’École Nationale de Lutherie in Mirecourt in the 1970s. Both died at a young age. And for each, the cause of death was related to heart issues. Lionel was 32 when his body rejected a transplanted heart in 1989. Pascal was 35 when he died of a heart attack in 1994 while working at his bench.

École d’Archeterie de Mirecourt & Bernard Ouchard

Any serious discussion of Pascal Lauxerrois and Lionel Tasquier must first provide historical context. In 1970 the bowmaking profession appeared to be on its last legs, even in France. As Stéphane Thomachot wrote in Les Luthiers Français: Les Archetiers Contemporains (L & V Le Canu), during the 1960s there were only three or four professional bowmakers in the entire country. But that began to change in 1970 when l’École Nationale de Lutherie was opened in Mirecourt, a small city that had been the home of a number of renowned French luthiers and archetiers. One year later, l’École d’Archeterie was added. And Bernard Ouchard, a member of one of France’s most important bowmaking families, was persuaded to leave the Vidoudez shop in Geneva to be the teacher. (Roger Lotte took over in 1979.) The inspiration for these schools came from Étienne Vatelot and Jean Bauer, whose motivation was both idealistic and practical. Besides wanting to re-invigorate the proud French traditions for violin and bowmaking, they wanted to insure that there would be top quality luthiers and archetiers to work in the many violin shops throughout Europe. This vision coincided with the French Minister of Music’s desire to re-establish Mirecourt as an important crossroads for French culture.

Aerial view of Mirecourt, where l'Ecole d'Archeterie opened in 1971

Aerial view of Mirecourt, where l'Ecole d'Archeterie opened in 1971

Today we can look back on the decade that followed as the dawn of a renaissance. But at the time, who could have anticipated this? After all, the average age of those Mirecourt students was only 16 when they enrolled. And not surprisingly they displayed the usual strengths and vulnerabilities of typical teenagers. Moreover they were coming of age during the post-Woodstock era when defiance and rebellion were as pervasive as idealism and reflection. Yet they succeeded. Today’s best evidence of this is the very high quality of their bows, plus their enduring influence on younger bowmakers.

Throughout history, bowmaking has attracted a relatively small number of individuals. Usually they are unable to play a string instrument and their knowledge of classical music is limited. So why have they been drawn to this? Often it’s because they were following in their fathers’ footsteps. But it may also have something to do with the fact that bowmaking is so fundamental and pure, even with its inherent disparities. It requires both pragmatism and inspiration, analysis and impulse, respect for tradition and the audacity to risk something new. One must toil at the bench for hours at a time, engaged in the most painstaking tasks, literally breathing the red dust of one’s labor. (A few of today’s finest bowmakers are allergic to pernambuco dust, yet they do this anyway.) Those who strive to be professional string players can at least demonstrate a rationale for their chosen path. Even those who make violins are able to convince others of the beauty and utility of their work through the sound that their instruments can produce. But if you’re a bowmaker, it’s not so easy to justify your labors by the sound of one of your bows. And if you are not an accomplished player yourself, you have to rely on someone else’s instrumental skill. Unless you become a dealer, this profession offers no assurances of financial security. Yet in a way, this fortifies the virtue of one’s commitment.

As inspiring as this may be, it’s not what motivated most students to enroll in the Mirecourt bowmaking school during the 1970s. For generations, the French national education system has been rigorously selective during the first years of high school. To this day, the grades that students earn largely determine whether they will continue with an advanced “classical” education in college, or are recommended for trade schools where they learn skills that the government determines are beneficial to French society and culture. Students at these trade schools seldom come from well-to-do families, which may make them less likely to play a string instrument or to have a classical music background. L’École Nationale de Lutherie and l’École d’Archeterie were considered trade schools.

As inspiring as this may be, it’s not what motivated most students to enroll in the Mirecourt bowmaking school during the 1970s. For generations, the French national education system has been rigorously selective during the first years of high school. To this day, the grades that students earn largely determine whether they will continue with an advanced “classical” education in college, or are recommended for trade schools where they learn skills that the government determines are beneficial to French society and culture. Students at these trade schools seldom come from well-to-do families, which may make them less likely to play a string instrument or to have a classical music background. L’École Nationale de Lutherie and l’École d’Archeterie were considered trade schools.

The students were selected through an audition process intended to assess their aptitude for this kind of work, conducted by teachers from these two schools. Étienne Vatelot was also usually involved. Every year a small group (usually 3) would be chosen for the bowmaking school from over 200 candidates. Each of these “classes” would stay for 3 years, overlapping with other classes for continuity. The school was free, including the barracks-style dormitory. Many of the students moved to private accommodations after a year or two. These rooms were humble and unsupervised, and they cooked for themselves because they couldn’t afford restaurants. But life was good because of the comradery and the independence that these living arrangements offered. Like most teenagers, they could party with zeal and didn’t always get a lot of sleep. But almost all of them were quite diligent and committed to their work.

At age 46, Bernard Ouchard and his wife had been enjoying a comfortable life in Geneva. He had a prestigious position as the resident archetier with the Vidoudez shop, one of the most important establishments in Europe at that time. But he grew frustrated having to devote so much of his time to repairing old bows rather than making his own. He also never got over his deep sadness when his father, Emile Auguste, decided to move to America when Bernard was just 21. In addition there were lingering emotional scars from his days fighting in the Indochina war. So when Étienne Vatelot pressured him to accept the position at l’École d’Archeterie, he agreed, despite his Swiss wife’s reluctance to live in Mirecourt. He was consoled by the fact that he’d be returning to the city of his birth where his family had lived for generations. Also the prospect of teaching highly motivated young bowmakers helped assuage his disappointment that his own sons had decided not to continue the family tradition of bowmaking.

Not everyone could have handled the challenge of overseeing a workshop of kids who were at the age when it’s normal to question authority. Perhaps as much as anything, it was Ouchard’s authenticity that enabled him to establish credibility and rapport. Given his professional stature, they addressed him as “maître.” But he didn’t put himself on a pedestal. He’d invite the students for lunch on Sundays, and they would often meet him at La Vosgienne, a nearby bar. He even took the 15-year-old Éric Grandchamp to the local billiards hall to teach him carambola! He had friendly nicknames for many of them: “P’tit Jean” (Grunberger), “Blâmont” (Duhaut), “Toulouse” (Muller), and “Chatou” or “l’Artiste” (Nehr). However he could be so strict and brusque that his sharp comments would make some of them cry.

Gold-mounted violin bow by Bernard Ouchard for the Vidoudez shop in Geneva

Gold-mounted violin bow by Bernard Ouchard for the Vidoudez shop in Geneva

While the students respected Ouchard, they were aware of his flaws – such as his unequal treatment of Sylvie Masson because she was a girl. It was also no secret that he drank too much, which may have contributed to his death in 1979. Yet as they now look back, they are even more grateful, not just for his knowledge and steadying influence, but for the confidence he helped them find. For many of them, he was much more than a teacher. And even now, nearly four decades after his death, his influence is palpable. For Jean-Pascal Nehr, “it’s as if I still have to prove myself to him.”

Bernard Ouchard was not a typical pedagogue. But no one questioned his expertise, skill, and devotion. He allowed the students to be independent and creative so long as they didn’t stray from the “classique” framework he learned from his father. His words were blunt and basic. Gilles Duhaut says, “When we showed him something, it was either good or it wasn’t. He rarely explained WHY things should be done in a certain way.” As a result, they did what students of most “old school” teachers have done – just as Josef Gingold’s students did when we studied violin with him around the same time. They helped each other by “reading between the lines” and filling in a lot of the detail that Ouchard often didn’t provide. Though almost all of them were supportive of each other, there was competition, even rivalries. But this only sharpened their acumen and accelerated their progress. There was also an unspoken hierarchy with the older students usually taking the initiative. And as they would graduate, others would assume those roles. As a result, an important tradition was forming and already evolving.

The days were divided between high school classes and bowmaking – usually four hours of each, five days a week. After the school day was done, many students would work on their bows at makeshift benches they would set up at home. Sometimes the older ones would persuade Ouchard (who had the only key) to let them use the school’s workshop at night. When he would agree, it was often with the caveat not to trust artificial light.

Bernard Ouchard loved classical music, as evidenced by his collection of nearly 250 vinyl records. He also enjoyed singing excerpts from his favorite operas. From his years at the Vidoudez firm, he developed close relationships with many string players, including Ruggiero Ricci, his hero. These are among the clues that suggest that Ouchard considered the bow to be not just an elegant and effective tool, but a tool that has a vital musical purpose.

Jean-François Raffin believes that the bows Bernard Ouchard made during the years he was teaching in Mirecourt are among his best – more refined than those that came from his bench at the Vidoudez shop. Perhaps he was finally free to follow his own impulses rather than what Vidoudez favored. But could it also be that this uniquely talented group of teenagers was challenging him to “bring his A-game?”

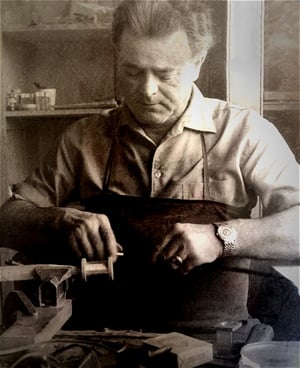

Pascal Lauxerrois

Pascal was related to Jehane Lauxerrois, the daughter of a fine cellist and the mother of Étienne Vatelot. His father, Jean-Paul, was an archetier – a good one. Pascal was therefore steeped in some of the profession’s traditions long before he went to Mirecourt. When he turned 16, he enrolled in the violinmaking school. A year later he transferred to the bowmaking school where his prior exposure gave him a leg up on the other students. Gilles Duhaut remembers that “Pascal’s progress was so fast that he reached the standard that was expected after two years in only four months. He also understood the characteristics of the wood quicker than the rest of us.” While a few of these teenagers may not have been sure at first that they wanted to devote their lives to bowmaking, Pascal knew immediately. He thrived at l’École  d’Archeterie not just because of the challenging interaction with the other students, but because Bernard Ouchard proved to be the kind of male authority figure who brought out his best. Though things could seem black and white with Ouchard, he was honest and fair. He judged Pascal’s work, nothing more. And despite his unvarnished criticisms, he was caring.

d’Archeterie not just because of the challenging interaction with the other students, but because Bernard Ouchard proved to be the kind of male authority figure who brought out his best. Though things could seem black and white with Ouchard, he was honest and fair. He judged Pascal’s work, nothing more. And despite his unvarnished criticisms, he was caring.

Pascal was reserved until he got to know you. He was also highly sensitive and exceedingly humble. He would never push himself on anyone or call attention to his exceptional talents. Gilles Duhaut recalls that when someone would seek his opinion, he’d say, “You can’t ask me because I don’t know enough.” But then he would be extremely helpful in his typically modest way. From time to time, his vulnerability and self-doubt would surface. His wife, Séverine, still remembers his anguish over whether a bow was good enough. When players would try his bows, he’d have to leave the room because he feared that their faces, if not their words, would reveal disappointment. It’s so easy to see why Jean Grunberger would say that “everyone had special feelings for Pascal.”

Though Benoît Rolland and Pascal didn’t overlap at Mirecourt, they worked together during the mid-1980s when Pascal would regularly visit Benoît on the island of Bréhat, off the coast of Brittany. Benoît recalls, “Pascal had a sharp and quick intelligence along with an incisive sense of humor.” He was also uncommonly generous. Charles Espey says, “When I first came to Paris and didn’t have a place to stay, Pascal let me stay in his apartment even though he barely knew me then.”

According to Gilles Duhaut, “Ouchard was always encouraging us to be quick, but without ever sacrificing quality. Pascal worked more quickly than almost everybody, and the quality was always very nice.” Marc Rosenstiel, a violinmaker who shared a shop with Pascal in Grenoble from 1986-1989, recalls that he could work virtually non-stop for twenty-four hours at a time. Once when he was late filling an order for a bow, he worked day and night, finishing it in just two days!

Pascal was always “in his world” while working, sometimes unaware when people would speak to him. He would often have the radio tuned to France Culture because he felt he couldn’t take time away from his bench to read as much as he wanted. He also listened to all kinds of music while he worked. He particularly loved Haydn and Bach.

Pascal Lauxerrois gold-mounted violin bow

Charles Espey was the first to tell me that Pascal had a special gift for expertise. According to Sylvain Bigot, Pascal was “a fabulous expert-to-be.” Bernard Millant himself referred to him in a certificate as “mon collègue Pascal Lauxerrois.” Jean-François Raffin recalls that Pascal would frequently visit him for long discussions about bows by the great masters – something that never happened with Bernard Ouchard. “I was very sorry to hear of his death! For me it was a disaster because there was nobody else in France who had this passion for expertise, like me.” (This was before he met Sylvain Bigot and Yannick Le Canu.) Pascal’s wife, Séverine, relates that after working all day at the bench, he could stay up all night studying historic bows. There’s no doubt that this informed and elevated his own work. Jean-Pascal Nehr goes even further. “When Pascal would study old bows, he’d look beyond obvious stylistic characteristics and focus on the smallest details. He’d then try to incorporate them in his own bows. Of course we all want to do this. But you can only incorporate what you’re able to see!”

Experts tell me that being a great bowmaker is more than what you can do with your hands, more than how you’ve refined your personal taste. It’s also about all the things you’ve learned from countless hours spent studying bows by the great masters. Jean-François Raffin does not hesitate. “For me, Pascal was a great bowmaker.”

A viola bow by Pascal Lauxerrois

The viola bow pictured below was made around 1982. In the head and stick, we see the influence of Peccatte and Tourte, though the head also reminds Benoît Rolland of his own style from their days working together in Bréhat after Mirecourt. According to Jean-François Raffin, the frog is similar to Voirin, as is the camber. “It’s very good; not too much by the head.” With whalebone lapping, the weight is 67 grams, and the balance point is 19.2 cm. The length of the stick is 72.8 cm, and it measures 0.155” on the deflection machine developed by William Salchow. It is very responsive and athletic though also dolce when the music requires it. It is “quick” but never sharp or hard, as some of Sartory’s later bows can be. A fine player can explore a wide range of shadings and articulations with this bow. For instance, one can play spicatto above and below the middle of the bow, in any tempo or dynamic. For a concerto with orchestra, I might choose a bow by Sartory or Vigneron-père. But for any of the Beethoven or Bartók string quartets, this bow by Pascal Lauxerrois inspires as much confidence as a Kittel or Dominique Peccatte.

Pascal Lauxerrois viola bow. The balance point is 19.2 cm and length of stick 72.8 cm.

“The Mirecourt way”

Bernard Ouchard steadfastly advocated the “classique” tradition he learned from his father, Emile Auguste. However he didn’t convey his techniques and overarching philosophy in a lucidly articulated manner. Nevertheless his students ultimately absorbed what some now refer to as “the Mirecourt way.”

There was no formal syllabus at l’École d’Archeterie. But the basic plan was well conceived, though it could vary from year to year. The first 1-2 weeks were devoted to making the tools and the metal templates which would later provide precise measurements for the violin, viola, and cello bows. (No bass bows were made there.) Then for one month the students would plane 30 sticks each. This was followed by learning how to bend the sticks properly, then making small corrections with the plane. Next came the head and mortices. Then the frogs – again, 30 of them. Sometimes Ouchard would alter the routine by assigning the students to different rooms – one for the stick, the other for the frog. After 15 months the students would finish their first bows. Some took even longer.

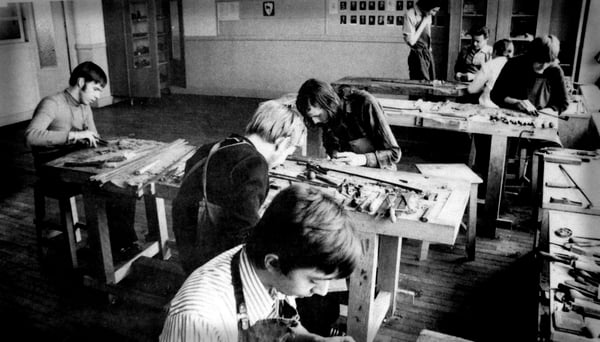

Mirecourt’s Ecole d’Archeterie in the academic year 1973–74. Clockwise from far back: Wilfred

Mirecourt’s Ecole d’Archeterie in the academic year 1973–74. Clockwise from far back: Wilfred

Hakoune (standing), Professor Bernard Ouchard, Sylvie Masson, Martin Devillers, Stephane Muller,

Benoît Rolland, Jean-Yves Matter and Gilles Duhaut. Photo: courtesy Sandrine Raffin

One of the reasons why Bernard Ouchard’s approach worked well was because these students were unusually attentive and resourceful. Nothing they showed to Ouchard would escape the scrutiny of the others. Indeed, every step of the bowmaking process was influenced by the small triumphs and failures of those working quietly at the nearby benches. The students would sometimes make chisels, planes, and knives for each other. (Gilles Duhaut’s planes were especially popular.) They would also share unique personal techniques that they’d developed – such as the one that Pascal Lauxerrois used to carve the head and le bec with rare precision and refinement. In all sorts of ways, the students benefited from each other’s knowledge, skill, and imagination.

Even though Ouchard encouraged creativity and initiative, he insisted on certain norms. While he would allow small deviations, everyone’s templates had to be similar to his. He also made it clear that a bowmaker must take responsibility for every aspect of the sticks and frogs. The buttons and ferrules were exceptions. Éric Grandchamp surmises that one reason for this may be that the school didn’t have the appropriate lathe during the first years. Though Ouchard urged everyone to work rapidly, he didn’t allow shortcuts. Therefore the notion of hiring others to make your frogs – or using unfinished, manufactured frogs – would have been unthinkable.

Since the school’s budget was limited, the materials that were provided were not always the finest. In the beginning, the only tools were those that had been donated by the Gillet family, and the wood came from Bazin’s attic. Later a local merchant named Gerome supplied wood which was, at best, inconsistent. Somewhat better wood later came from Jean Schmitt in Lyon. When certain students felt they were ready for wood of the highest quality, they’d buy it themselves, usually from Bazin or Dupuys.

L’Ecole Nationale de Lutherie, Mirecourt, where Lionel Tasquier initially studied violin making

L’Ecole Nationale de Lutherie, Mirecourt, where Lionel Tasquier initially studied violin making

Only nickel-silver was provided, again because of the cost. On rare occasions when students wanted to use more expensive metals for the ferrules, buttons, and underslides of very special sticks, they would buy the silver or gold themselves. As for lappings, they used mostly nickel-silver wire of various diameters. They also experimented with lizard, shark, fish skin, leather, and tinsel/silk. Naturally there was heated animal glue, though white glue was also used for the grip and tip. Crazy glue was relatively new – and Ouchard detested it. They often used nitric acid to darken the sticks. And Jean Grunberger recalls that they were later told about ammonia, though not by Ouchard. Their varnish consisted of gum-lac with a little oil.

The weight of a bow is very important to most string players. Indeed, there can be strong preferences about whether it should be more or less than the average weights for violin, viola, and cello bows: 60, 70, and 80 grams respectively. According to the “classique” tradition, the scale should be used only after a bow is finished. In Mirecourt, it wasn’t used even then! Gilles Duhaut remembers that the shop’s scale was crude and inaccurate. “We used it only to weigh the letters that were to be taken to the post office. Ouchard’s process was not so empirical. It was more by feel and experience.” When I once asked Jean-Pascal Nehr how he knows when the weight is right, he simply said, “The wood tells you.”

Although Bernard Ouchard did not prevent students from developing their own styles, particularly for the head of the bow, most of them deviated from the “classique” style only after they left Mirecourt. While they were still there, they were expected to work within certain parameters, such as the recommended widths for the base of the frogs: 13.3 cm for violin, 14.3 for viola, and 15.3 for cello. It may come as a surprise that Ouchard never urged the students to study bows by the great masters. And he would only rarely talk about how minute variations in the camber, the wood density, and the balance can influence a bow’s playing characteristics. This only made those who were already curious about such things even more curious. These included Benoît Rolland and Pascal Lauxerrois. For others, this curiosity developed later.

All students at the Mirecourt schools were expected to demonstrate basic instrumental proficiency in order to graduate. Unless they were already accomplished players, they were required to take private violin lessons and perform a short piece in public as part of their final exam. This was no problem for those who could already play quite well – Christophe Schaeffer, Martin Devillers, and Benoît Rolland, for example. But for others, this was a challenge. Even though Bernard Ouchard didn’t play a string instrument, he accepted the school’s policy. According to Benoît, “He knew that playing was a real plus in this work because it tremendously helps to understand the functionality of a bow.”

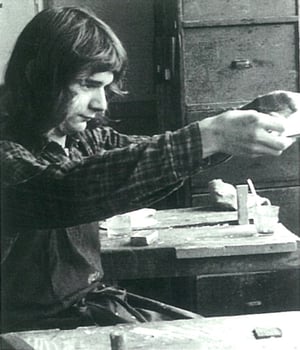

Lionel Tasquier

The idea to include Lionel Tasquier in this article emerged from a conversation with Bernard Sabatier about Pascal Lauxerrois. It was difficult for him to talk about one of these bowmakers without talking about the other! When I recalled the stories that Benoît Rolland had previously shared with me about Lionel, it seemed right to broaden the focus. For here are two archetiers who are related not only by their remarkable talent, but by their obscurity, the scarcity of their bows, and the tragedy of their early deaths.

The idea to include Lionel Tasquier in this article emerged from a conversation with Bernard Sabatier about Pascal Lauxerrois. It was difficult for him to talk about one of these bowmakers without talking about the other! When I recalled the stories that Benoît Rolland had previously shared with me about Lionel, it seemed right to broaden the focus. For here are two archetiers who are related not only by their remarkable talent, but by their obscurity, the scarcity of their bows, and the tragedy of their early deaths.

Lionel attended the violinmaking school in Mirecourt for three years but didn’t graduate because they believed he had been disrespectful to one of the instructors. Disillusioned and despondent, he gave up violinmaking and worked for two years at a newspaper factory where he operated the printing presses. This was exhausting and dangerous work that led to a heart attack at age 25. Knowing that Lionel was very interested in bows, Benoît Rolland invited him to learn bowmaking. And before long, Lionel was working beside his mentor in Benoît’s Paris studio. In just two years, he became “one of the most gifted bowmakers I have ever seen.”

In 1982 when Benoît moved to the island of Bréhat off the coast of Brittany, Lionel continued to work alongside him for another year. During that period, Pascal Lauxerrois would often come, and the three of them would work alongside each other. With the support of Bernard Sabatier, Lionel then opened his own small shop on rue de Budapest in Paris. But suddenly everything changed when he had a second heart attack… then a third… and finally a by-pass operation. When he continued to decline, he was put on the waiting list for a heart transplant. And after one year, he finally received the new heart. But his body rejected it and he died within a week at the age of 32.

Lionel Tasquier and Jean Grunberger knew each other in Mirecourt when Lionel was in his third year of the violinmaking school and Jean was in his first year of the bowmaking school. Jean describes him as “an unconventional guy with a true artist temperament.” He was introspective and loved to paint and write poetry. He had a serious girlfriend, Fanny, but didn’t have many friends besides those who shared his passion for bowmaking or the guitar. He was able to share both of these pursuits with Jean Grunberger and Gilles Duhaut, both fine guitarists. They recall that Lionel was not only an excellent player but composed a number of pieces. These were not simple chordal accompaniments to popular songs, but challenging and complex solo works. He didn’t write them down because he never learned how to read music.

Benoît Rolland’s influence helped Lionel to embrace the concept that bowmaking and music-making are “in harmony” with one another. Though the bowmaking process takes place in a private and unassuming setting that is far removed from the regalia of the concert hall, many believe that it should not be totally detached from the musical masterpieces whose expressive demands it will eventually serve.

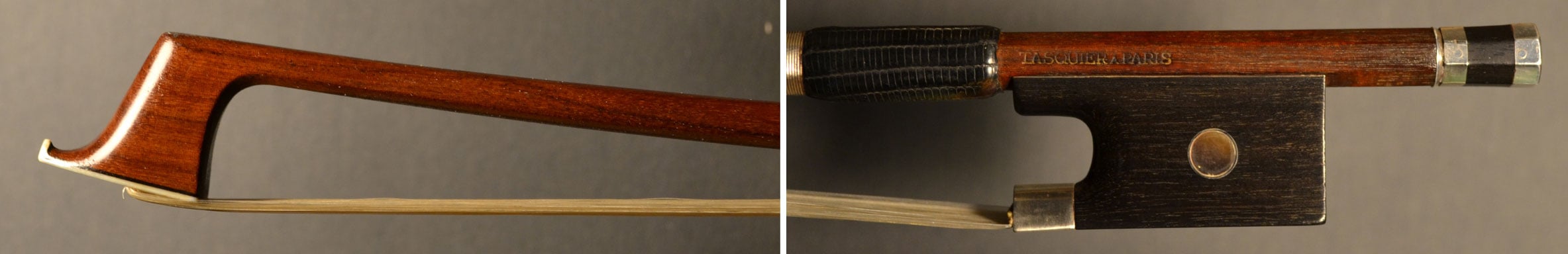

Lionel Tasquier violin bow, Paris.

In Lionel’s bows, one appreciates the strong fundamentals of his training. They also reveal that he was not influenced by any particular style from the past. One reason was because he had not been exposed to many old bows, which limited his appreciation of them. Another reason was that he was tenaciously original. As Jean Grunberger puts it, “Lionel went his own way, according to his feelings.” This may explain certain unusual personal touches, such as the Japanese designs on the frog of a bow pictured in Les Luthiers Français: Les Archetiers Contemporains (L & V Le Canu). But not so unlike many of the masters, he was searching for a balance between an adherence to basic principles and his penchant for personal expression. He was still searching for that balance when he died.

It would be wrong to leave the impression that Lionel Tasquier and Pascal Lauxerrois were equals. Most of their contemporaries feel that Pascal achieved a higher degree of sophistication before his death, probably because of his obsession with old bows. But while Lionel’s gift may not have matured as much by the time he died, his raw talent, creativity, and technical skill were just as remarkable.

Coda

When I think about all the students I’ve taught over the years, including two who died unexpectedly, it somehow feels right to have in my hands the viola bow by Pascal Lauxerrois that was featured in Part 1 of this article. It’s a bow that was made by an incredibly talented young man in his early 20s who died far too soon. Yet he was able to produce THIS amazing bow – a bow that reassures us that anything is possible when gifted individuals, no matter their age or circumstances, summon the resolve and passion to give their absolute best.

These beautiful bows by Pascal Lauxerrois and Lionel Tasquier also provide disquieting reminders that being a talented and dedicated 20- or 30-year-old is no guarantee that you’ll reach your 40s, 50s, or 60s. These bows also caution us that last week’s concert, the lesson we gave yesterday, or the bow that we finished only an hour ago, could be our very last – perhaps the one that people will remember us by.

Students of l’École d’Archeterie de Mirecourt

1971-1974: Benoît Rolland, Jean-Yves Matter

1972-1975: Stéphane Muller, Wilfred Hakoune

1973-1976: Gilles Duhaut, Sylvie Masson, Martin Devillers

1974-1977: Jean-Pascal Nehr, Christophe Schaeffer, Didier Claudel

1975-1978: Pascal Lauxerrois, Jean Grunberger, Stéphane Thomachot

1976-1979: Michel Jamonneau, Jacques Poullot

1977-1980: Éric Grandchamp, Arnaud Suard, Georges Tepho

1978-1981: Marielle Gobin

Heartfelt thanks to the following individuals for sharing their recollections, photos, and expertise: John Aniano, Sylvain Bigot, Alexander Caballero, Martin Devillers, Gilles Duhaut, Charles Espey, Olivier Fluchaire, Éric Grandchamp, Jean Grunberger, Séverine Lauxerrois, Loïc Le Canu, Susan Lipkins, Sylvie Masson, Pierre Mastrangelo, Stéphane Muller, Jean-Pascal Nehr, Jean-Marc Panhaleux, Jean-François Raffin, Benoît Rolland, Marc Rosenstiel, Bernard Sabatier, Georges Tepho, and Stéphane Thomachot.