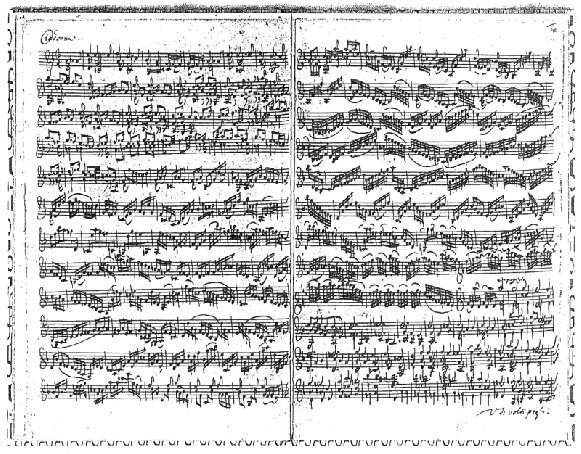

As of Wednesday, J.S. Bach would be 327. In honor of his special day, I thought it would be fitting to give homage to one of his greatest works – arguably one of the greatest masterpieces of all time, especially for a stringed instrument – the Chaconne.

The final movement of the D minor Partita (S. 1004), the Chaconne, is, without hesitation, a masterpiece. Joshua Bell commented that it is “not just one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, but one of the greatest achievements of any man in history. It is a spiritually powerful piece, emotionally powerful, and structurally perfect.”[1]

I cannot approach this human masterpiece without babbling in the face of greatness. There are numerous essays and analyses of this piece done by more qualified and more eloquent people than me. But, in honor of the composer’s birthday, I will share just a few of my personal thoughts in tribute.

The Chaconne is disciplined. A chaconne consists of a series of melodic variations over a continually repeated “ground bass” line. In the case of Bach’s composition, the ground bass repeats 64 times during the 15-minute duration of the work. Nonetheless, the melodic variation is boundless. Philip Spitta, the renowned Bach scholar of the 19th century, says of this variety:

From the grave majesty of the beginning to the 32nd notes which rush up and down like the very demons; from the tremulous arpeggios that hang almost motionless, like veiling clouds above a dark ravine ... to the devotional beauty of the D major section, where the evening sun sets in a peaceful valley: the spirit of the master urges the instrument to incredible utterances. At the end of the D major section it sounds like an organ, and sometimes a whole band of violins seem to be playing. This Chaconne is a triumph of spirit over matter such as even Bach never repeated in a more brilliant manner.

This incredible variety within the Chaconne has been seen to be representative of the full range of human emotion and experience. Some even see the Chaconne as a microcosmic expression of life – Bach is thought to have composed the piece after the death of his first wife, Maria Barbara.

The Chaconne is cyclic. The entire piece is in a giant ABA form with the two massive D minor sections framing the hymn-like D major middle. In his autobiography Violin Dreams, Arnold Steinhardt muses on this tripartite structure as well as other triplicate structures within the piece; he wonders if these could be evocative of the Trinity. Bach was notably Christian and dedicated many of even his secular pieces Soli Deo Gloria, so Steinhardt may be on to something. For my part, I see both the cyclic structure of the piece and the continually repeated ground bass to be expressive of the omnipresence of the divine in every circumstance of life.

Finally, the Chaconne is a dance. The piece is so imposing with its length, towering chords, and technical difficulty that it can be easy for us to be daunted by its grandeur. Further, thinking of the piece as a dance may seem to diminish the gravity or profundity of the composition. But the opposite is actually true: by composing such a powerful masterpiece in the form of a dance, Bach brings freedom, freshness, and a distinctly human element to his statement. Somehow the dance element of the piece makes it accessible.

Anything that I can say about the Chaconne is limited and ineffectual. Truly, this piece speaks of something that my words cannot. I defer.